Review: An In-Depth Analysis of Celtic vs. Aberdeen – The Final Victory

Triumph in the Final: Aberdeen’s Victory

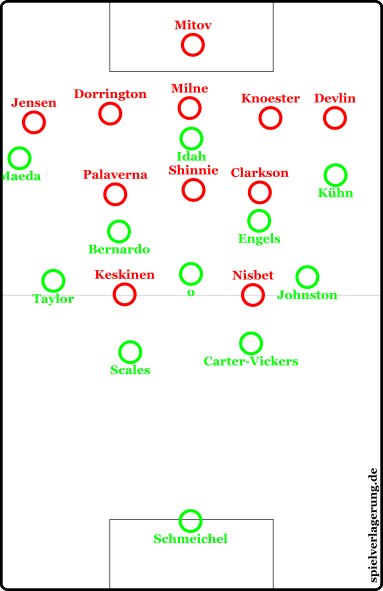

Jimmy Thelin adjusted his team’s tactical approach, deploying them in a different formation when out of possession. Instead of the previous flat 4-4-2 system, Aberdeen now operated in a 5-3-2.

The switch to the new formation brought several distinct advantages, which we will explore in more detail below.

Personnel Changes

In the newly adopted 5-3-2 formation, Keskinen and Nisbet formed the striking duo. Their primary task was, once again, to neutralize the opposing holding midfielder, McGregor, effectively disrupting the opponent’s build-up play. In central midfield, Shinnie assumed the role of the defensive anchor, supported on the left by Clarkson and on the right by Palaversa in the midfield trio.

In the newly adopted 5-3-2 formation, Keskinen and Nisbet formed the striking duo. Their primary task was, once again, to neutralize the opposing holding midfielder, McGregor, effectively disrupting the opponent’s build-up play. In central midfield, Shinnie assumed the role of the defensive anchor, supported on the left by Clarkson and on the right by Palaversa in the midfield trio.

The newly organized five-man defensive line consisted of Devlin, Knoester, Milne, and Dorrington. Jimmy Thelin made the tactical decision to initially sacrifice offensive prowess by placing Morris and Gueye on the bench. Both players were slated for later substitutions, where they would play pivotal roles.

In their stead, Milne, a center-back, and Devlin, operating as a full-back, were included in the starting lineup, reinforcing the team’s defensive structure from the outset.

Structural Change and Its Consequences

Not only personnel changes but also structural adjustments had a significant impact on the course of the game. Especially in defense, Aberdeen showed a much-improved organization, which helped the team control Celtic’s attacks more effectively.

In this context, we have thoroughly analyzed the key aspects to provide a clear overview of the advantages brought by the formation change.

1. Numerical Advantage Near the Ball

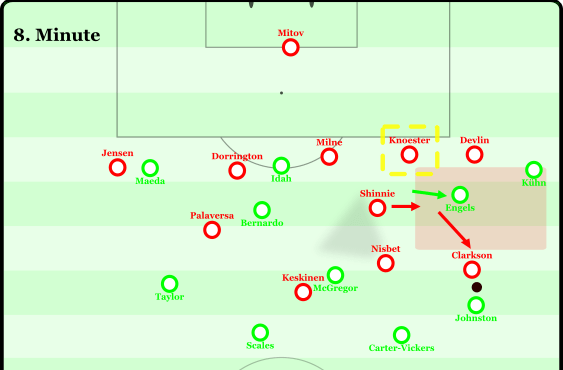

Compared to the first leg, Aberdeen managed to create a 4-versus-3 numerical advantage on the wings more often, instead of having to engage in 3-versus-3 duels as before. Their defensive setup on the wing worked like this: the number eight marked the opponent’s full-back, Shinnie as the defensive midfielder took care of the ball-side number eight, doing an excellent job, while their own full-back covered Celtic’s winger.

This often allowed the half center back to act as a free man and join the defense as an additional player.

At times, Nisbet or Keskinen also dropped back to the ball-side to help compress the space even further. The main difference compared to the 4-4-2 was that Aberdeen abandoned marking the far-side winger and instead had an extra player on the ball-side.

While this created more space on the far side, it was only a minor risk for Aberdeen since Celtic usually plays with few switches of play.

Celtic aims to exploit the space behind Clarkson. Engels moves out to the wing, with Shinnie following him. Nisbet’s deeper positioning cuts off the diagonal run into the center. The player outlined in yellow is the free half center back, who can cover any potential runs.

2. Improved Passing of Responsibility

Another key point was the improved handover and coverage, which directly built on the previously described advantage. Since the half center back acted as a free player, he was able to timely pick up deep runs—whether from the full-back or the number eight. This allowed Shinnie, as the defensive midfielder, to often maintain his position without having to defend constantly by stepping back.

The communication and organization within the defense also improved significantly. Depending on the positioning of the number eight, the team could hand over responsibilities flexibly, increasing their adaptability. Overall, Aberdeen was very well organized and could effectively manage Celtic’s numerous rotations.

An example of this is the horizontal rotation between Celtic’s number eight and their outside forward: while the outside forward operated high in the half-space, the number eight moved wide and high into the wide area. In a traditional 4-4-2 system, this would have caused major marking problems, creating a 2-versus-1 scenario against the full-back on the outside. The number six would have had to follow into the wide area, leaving space open in the half-space as players left their positions.

Thanks to the half center back, this wide attacker could be covered, allowing the full-back to press outward and Shinnie to hold his position steadily.

3. Defending Forward / Covering the Back of Your Teammate

Aberdeen was also able to manage the sliding up much better, which gave them a clear advantage in many situations: the full-back could push out much more aggressively without the distance between defenders becoming too large, because the extra player effectively covered the gap.

This was especially important when Celtic quickly opened the game through switches of play or used enticing passes to draw Aberdeen’s players into the center, and Shinnie couldn’t shift in time to the ball-side to take over the number eight. In these cases, Aberdeen was able to react flexibly.

On the right side, Clarkson stayed with the number eight, while Devlin pressed Johnstone and Knoester often slid up to mark Kühn, who frequently rotated into the half-space. On the opposite side, Dorrington regularly pressed aggressively on Bernardo.

However, sometimes communication was lacking, as in the 76th minute when Shinnie and Dorrington both pressed out on Bernardo, forcing Jensen to pick up the inside-running Taylor, which meant he couldn’t cover Yung on the outside.

Despite this, Aberdeen managed to remain stable even during quick switches of play and consistently closed down spaces—unlike in the first leg, where these switches often caused problems for them.

4. box defense

Aberdeen also showed greater stability in defending the penalty area. Milne was often able to act as an extra player at the near post and was very present. Even when Celtic managed to work the ball behind the last defensive line and into the box, Milne was consistently able to clear all crosses safely during the first half.

This was partly because Aberdeen played much deeper compared to the game ten days earlier, allowing them to better adapt to actions inside the box. Additionally, with nominally six players in the central area—three center-backs and three central midfielders—they had more personnel in the box.

The principle of “many legs,” meaning more players in the box, increased their presence and made it harder for the opponent to execute plays, as there were more bodies and defensive options available. Overall, this improved connection in the box further stabilized their defense.

Disadvantages of the 5-3-2 System

We have now outlined the advantages of the 5-3-2 system. However, there were also aspects that worked against this formation.

By using the 5-3-2, Aberdeen defended deeper in their own half, which sometimes allowed Celtic to build their play near the Dons’ penalty area.

This was also because Aberdeen showed very few sequences of high pressing, focusing primarily on not conceding goals. The chosen formation proved less suitable for effective high pressing. In the first half, Aberdeen made only two attempts to switch to high pressing, but these transitions showed clear weaknesses. Celtic was able to resolve both situations easily with a simple layoff to McGregor.

The reason for this lay in the roles of the two forwards, who each had to press Celtic’s center-backs. Since the rest of the team did not push up quickly enough, McGregor remained unmarked, as the far-side forward was unable to apply pressure on him.

This was different from the previous game, where Aberdeen could quickly shift from the 4-4-2 system into a 4-2-4, providing more players for pressing.

How Aberdeen Could Have Gained Control in High Pressing: Our Solution

We thought about the best way to press Celtic high up the pitch and concluded that it is not impossible—in fact, it can be very effective to apply high pressure. The first half showed that Aberdeen, by defending deep, was constantly exposed to Celtic’s pressure without finding relief through their own chances after winning the ball high up or at least through sustained possession phases.

This problem was further amplified by the 5-3-2 formation, as Aberdeen often had very long distances after regaining possession, which is definitely a drawback of the 5-3-2 system. Since one of the two forwards, usually Nisbet, dropped deep to help defend, Keskinen was often left alone against two center-backs and sometimes McGregor. He had to try to hold the ball, but this was rarely successful due to the delayed support from teammates. This frequently led to turnovers and gave Celtic the chance to increase the pressure even more.

This situation allowed Celtic to continuously build up pressure and force set-piece situations, one of which led to a goal in the 38th minute. A more effective, higher pressing strategy would have relieved Aberdeen defensively while also providing greater control and offensive opportunities.

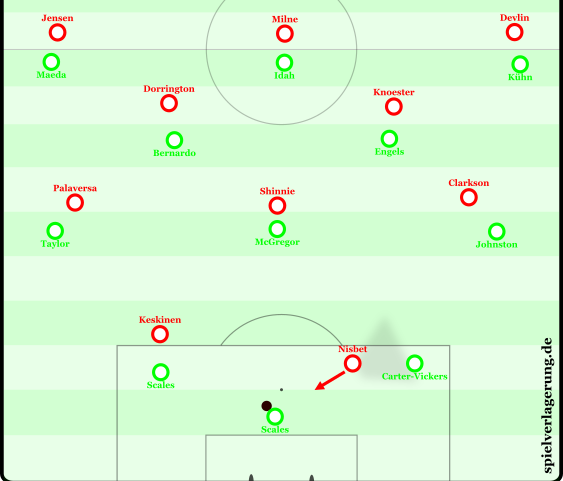

Our approach for effective high pressing would be as follows: We would follow one of the biggest current trends, which has been established the world of football. This approach focuses on preventing the opponent from finding a free player—a crucial factor given Celtic’s high individual quality on the pitch. Specifically, we would implement man-to-man pressing across the entire field to disrupt the opponent’s flow early and deny clear passing options and layoff plays.

Concretely, our pressing plan would look like this: The two forwards would press the center-backs, while the number eights, Palaversa and Clarkson, would step up to press the opposing full-backs. Shinnie would put direct pressure on McGregor, Celtic’s defensive midfielder. To cover Celtic’s number eights, Aberdeen’s half center-backs would push up and take over marking these players.

Our idea of aggressive man-to-man pressing: Nisbet would cautiously press Schmeichel while keeping Carter-Vickers in his cover shadow.

Although this means that Aberdeen will face a 3-on-3 situation in the last line, the focus is on applying so much pressure on Celtic’s first build-up line that they cannot exploit the three-against-three effectively.

A key question here is whether and how to press the goalkeeper, as Celtic often involve him in their build-up play. Our plan would be to generally avoid pressing the goalkeeper directly and only trigger pressure situationally with one of the two forwards.

If Celtic tries to solve the pressure with a layoff pass, it is crucial that the winger does not immediately press the layoff recipient (the center-back), as happened in the previous game. Otherwise, Celtic could use another layoff to bypass the press.

Instead, Shinnie would follow the layoff pass to the center-back and run him down. In this example Keskinen should try to recover quickly and track back to mark McGregor tightly. This way, we could effectively disrupt the layoff play because pressing from the center would actively force Celtic to the wing, where Aberdeen could establish direct control.

Celtic’s Play down the Wing with Lots of Rotations

Celtic had a lot of possession (84% in the first half) but still struggled significantly to create clear scoring chances against the 5-3-2 formation, despite fielding their strongest lineup and showing good tactical ideas. Like in the previous game, they played from a 4-3-3 system, but this time with their regular starters. On the wings were Kühn and Maeda, with Idah in the center forward position. Engels replaced McGowan on the right number eight, while Carter-Vickers and Scales came in for Nawrocki and Trusty in central defense. The full-backs Ralston and Schlupp were replaced by Johnston and Taylor.

Overall, Celtic showed more variability in their rotations, partly due to the personnel used. Especially on the right side, players like Nicolas Kühn demonstrated flexibility and effectiveness, operating both in the half-space and wide areas. On the other hand, the changed defensive structure of Aberdeen also made things harder for Celtic.

On the wings, Celtic displayed a mix of effective and less successful rotations. While some movement patterns were indeed effective and added dynamism, others had little noticeable impact. Thanks to their new defensive setup, Aberdeen was able to defend these rotations in a targeted and effective way, preventing them from having a decisive influence on the game.

An example of this is the rotation between Bernardo and Taylor, where Bernardo dropped back to the full-back position and Taylor took over the number eight role. This horizontal position rotation, a typical element in Celtic’s play, proved relatively ineffective against Aberdeen. Unlike other formations and structural adjustments, this rotation brought only limited success. The Dons were able to control these movements through their adapted base structure and good organization, minimizing their impact on the game.

A particularly effective rotation was seen in the 8th minute. Johnston’s flat positioning pulled Clarkson out of his position, which was especially effective on Aberdeen’s right side. Arne Engels then moved into the wide area, overloading the zone with three players.

In general, it can be observed that Celtic’s rotations were particularly effective when they operated with three players in the wide area. This caused original positions to be abandoned, which created problems for Aberdeen. Especially Shinnie and the half center back struggled to cover the long distances, resulting in occasional organizational issues. For example, in the 4th minute, Engels rotated to the right-back position, Johnston stayed wide, and Kühn moved slightly into the half-space. This caused Clarkson to press Engels, leaving Johnstone temporarily unmarked.

For Aberdeen, it was extremely difficult to establish clear marking because both the half center back and the defensive midfielder had to cover large distances to neutralize the overload. Consequently, Celtic managed to use a layoff from Nicolas Kühn to put Engels into a promising position.

However, this was one of the few successful rotations and did not always work, as Aberdeen was very effective at defending while retreating. An example of a less effective rotation—one that had worked well in the previous game—was the full-back moving into the half-space while the winger came short. Especially on the right side, Devlin was able to calm these situations down with his aggressive pressing. He often won duels through strong challenges or forced Nicolas Kühn into a backward pass, which slowed down the attack’s momentum.

Horizontal rotations between two players often became effective only after a backward pass. A backward pass usually has the psychological effect of making the defending team think the situation is under control. This happens because defenders often assume the opponent is trying to switch play and start a new attack. As a result, the defending team begins shifting to the opposite side, briefly neglecting the ball-near side. Celtic used this cleverly by playing deliberate backward passes to their center-backs and then building new attacking patterns from there.

An example of this happened in the 16th minute: After a backward pass, the midfielder who had previously moved to the full-back position rotated into the half-space. This movement pulled his defender out of position and opened a passing lane to the outside, where the full-back moved. These movements created space and allowed Celtic to continue their attacks effectively down the wings.

Good ideas but no breakthrough

Celtic not only managed to combine their way almost to the byline through these movement patterns but also showed other promising approaches.

1. Involvement of the far-side number eight

As already mentioned, Celtic often positions the far-side number eight in the space typically occupied by a number ten. However, it has been increasingly observed that the far-side number eight shifts toward the ball-near side to create an additional passing option in the half-space. This proved particularly effective when the ball-near number eight made runs into depth. This movement enabled Celtic to transform their initial 4-vs-3 disadvantage on the flank into a 4-vs-4 situation.

Celtic often exploited the 4-vs-4 situation as follows: „from the outside to the inside and back outside.“ Kühn frequently drove the ball toward the center, forcing Aberdeen to compress their central defensive shape. Celtic then played the ball through a triangle – involving the far-side number eight, who was often unmarked because the half-center-back didn’t always step out to engage, while Shinnie focused on the ball-near number eight, effectively creating a 2-vs-1 – back to the flank, where a player rotated into space.

This element also provided Celtic with much greater control over the game. They were able to circulate the ball on the flank without Shinnie being able to intervene effectively in the 2-vs-1 or apply significant pressure. Additionally, the two number eights were able to combine effectively, as demonstrated impressively by Engels‘ shot against the post in the 63rd minute.

2. Attacking the Depth

A common tactic in the game was targeting Aberdeen’s half-center-back with deep runs. The goal was to pull the half-center-back wide or keep him tied up in the center, creating space for another deep run. Sometimes this forced the central defender Milne to move out wide to cover that player. But what Celtic really wanted was to force Shinnie and/or Clarkson to drop back and defend in the last line.

A clear example of this strategy happened in the 30th minute: The far-side midfielder moved again to the ball side, creating a 2v1 situation against Shinnie. Engels made a deep run toward the penalty area, pulling the half-center-back with him. This opened space that Bernardo and Johnston immediately exploited, while Shinnie and Clarkson were tied up in the last line.

Engels took advantage of the gap and moved into the free space. He tried to continue the attack with a pass to the oncoming Bernardo through a third player, but the pass was not accurate enough, so the chance didn’t lead to a shot.

Even during Engels’ shot off the post in the 63rd minute, which was mentioned earlier, this principle became particularly clear. Johnstone engaged both the half-back and Shinnie in the last defensive line, allowing Kühn, with his flat positioning, to pull Devlin out of his position. As a result, Aberdeen’s full-back, in this case Devlin, often had an awkward, too straight angle of approach. Kühn repeatedly took advantage of this skillfully to effectively initiate the attacking situation with a precise first touch and a dribble into the center.

3. Drawing the half-center-back out of position

As already mentioned, the goal was often to manipulate the half-back intentionally – and this was not done only through runs into space. Aberdeen frequently passed the central midfielder (the „eight“) to the half-back from a certain zone. Celtic tried to exploit this by drawing the half-back out, so they could target the space behind him, for example, with a deep run from the opposite-side midfielder.

This worked especially well on the left attacking side, where Dorrington often stepped out of the defensive line to defend. This allowed Celtic to use the space in behind or to pull Aberdeen’s full-back inside, thereby opening up the flank—for example, for the winger.

4. Switches into the far-side half-space

One aspect Celtic rarely used in the early stages was targeted switching into the far-side half-space. Since Aberdeen usually had one more player on the ball side, the far-side half-space was left unoccupied. Especially in the beginning, Celtic had several opportunities to shift the play diagonally into that area. However, toward the end of the first half, Celtic used this tactic more often and created a chance in the 28th minute—a long-range shot by Taylor.

In the second half, and also toward the end of the first half, switches into the half-space became more frequent. This was not only done by switching the ball from one side to the other but also through “small switches,” for example from the center, where Celtic deliberately lured Aberdeen into the center with targeted passes. This caused Aberdeen to compress the center and open up spaces—more on that later. This way, Celtic repeatedly managed to create promising one-on-one situations for Kühn and later Forrest.

Celtic’s layoff play as another aspect of their game

Celtic is characterized not only by their wing play but also by strong layoff play and targeted use of the third player. This approach was especially noticeable against high pressing and has been analyzed extensively. Even when facing a deeper defensive block, Celtic uses layoffs to bypass an additional line and, through a precise layoff, put a teammate into a favorable position with an open foot.

In the center of the pitch, this pattern was observed frequently throughout the season. A typical example is a midfielder laying the ball off from a central attacking midfielder (the “eight”) to the defensive midfielder (the “six”), freeing him up. This is because many teams, including Aberdeen, block the direct passing lanes to the forwards but don’t man-mark the defensive midfielder. This often means that the six cannot be found by a direct pass, but through a third-man combination, where he can operate with a movement advantage.

In Celtic’s 5-1 victory, this layoff play was more effective than in the final. The reason lies in the different tactical situations: against Aberdeen’s 4-4-2, Celtic could create a 3-versus-2 overload in the center through these layoffs, while in the final against the 5-3-2, it was a balanced 3-versus-3 situation.

In the second half, McGregor in particular was frequently involved through diagonal passes from the wing, actively participating to create overloads and dangerous attacks. It’s also worth noting that Aberdeen struggled at times to maintain their midfield organization as the match progressed.

The Second half

In the 66th minute, Brendan Rodgers made several personnel changes: McCowan replaced Engels, while Forrest came on for Kühn and Yang for Idah. This shift moved Maeda, who had previously played on the left wing, into the central striker role. With these adjustments, Celtic was able to create numerical superiority more frequently in midfield and initiate quick combination play in the space between the lines, as impressively demonstrated in the 68th minute.

Rodgers also made targeted tactical adjustments. Already in the first half, the team used the far-side attacking midfielder (the “eight”) in the number 10 zone with inviting passes. Bernardo often took on this role, as most of the play developed down the right side. These inviting passes had a dual effect: on one hand, they pulled Shinnie, Aberdeen’s central midfielder, out of his position in the middle, leaving the ball side short. On the other hand, this forced Aberdeen to defend the center more tightly, which in turn opened up space on the wings.

In the second half, Celtic intensified and refined this strategy, significantly increasing the pressure on Aberdeen. The focus shifted increasingly to attacking through the center, consistently forcing Aberdeen to adapt their defensive shape.

The main goal was to lure Aberdeen into concentrating their defense more centrally, thereby creating space on the flanks that Celtic could exploit consistently in their attacks. This often led to even-numbered situations such as 3-on-3, 2-on-2, or even isolated 1-on-1 duels. Celtic skillfully exploited these scenarios thanks to their individual quality and well-coordinated combinations, putting Aberdeen under great pressure.

Aberdeen also made adjustments, with Palaversa featuring more frequently in the defensive midfield (the “six”) and Shinnie moving to the right “eight” position. This change was likely driven by athletic considerations. Nonetheless, Shinnie and Aberdeen as a whole showed high discipline. It was particularly noticeable how consistently they shifted toward the far side in the second half to effectively mark the far-side attacking midfielder.

Aberdeen with limited output in possession

Despite Aberdeen’s disciplined defending, their play with the ball showed room for improvement. This was one of the main reasons for their limited possession. The match plan was straightforward: long balls aimed to avoid mistakes in buildup. However, the execution wasn’t always ideal.

The central midfielders (the eights) and Shinnie often positioned themselves slightly deeper to pull Celtic’s tightly man-marking midfield out of position. Nisbet was usually the target for the long balls, often dropping slightly back, while Keskinen took on the role of threatening in behind.

To secure second balls, the two fullbacks tucked in somewhat. This was only partially effective because Aberdeen’s midfield often stood very flat due to being pulled out wide, and the fullbacks only slightly moved inward. This left open spaces in central midfield where Celtic could collect second balls.

This was largely because Nisbet rarely won aerial duels. Additionally, Celtic defended excellently in their own half, showing excellent depth in their defensive shape, which made it difficult for Aberdeen to capitalize on the long balls.

Aberdeen’s tracking back and compact shifting to second balls was not always flawless either, allowing Celtic to create dangerous chances after winning possession. An example came in the 20th minute, when Aberdeen’s center backs expected a short pass, but Mitov played a long ball without clear intent. Celtic immediately intercepted it, and the ball bounced back like a boomerang, creating a dangerous situation for Aberdeen.

Aberdeen’s buildup structure was based on an asymmetrical 3+1 system. Knoester and Milne operated as central players in the back three, Dorrington shifted to left wing-back, and Mitov took a central role in buildup play.

Aberdeen rarely played out from the back on the ground, partly due to Celtic’s effective and well-organized pressing, but also because they prioritized minimizing risks in their own third. One example came in the 58th minute, when they attempted a flat buildup. This sequence was similar to patterns seen earlier in the first half: the wide midfielder Clarkson positioned himself broadly on the left side — which was lightly covered due to the asymmetry — to exploit space behind Celtic’s wingers. These spaces opened because Celtic applied pressure on the half-backs with their wide players.

Here, Aberdeen showed a promising approach: Nisbet dropped back, and through precise short passes with Gueye, they managed to shift play toward the far-side fullback. This approach could have been used more often in the first half with well-placed diagonal balls.

However, this also highlighted an area for Aberdeen to improve: precision and quality in their combinations. Instead of playing the ball accurately into Jensen’s stride, Gueye’s pass was slightly off, resulting in the ball going out of play.

Jimmy Thelin’s match plan to keep the game open as long as possible and then bring on attacking players late worked perfectly. In the 80th minute, he introduced fresh offensive personnel, bringing Morris, Palaversa, and Dabbagh on for Nisbet, Clarkson, and Dorrington.

Earlier, he had already subbed Gueye in for Keskinen, whose power added fresh energy and helped extend long balls. But Morris was particularly impactful. Together with Jensen, they formed their usual wing partnership and set up the equalizer: Jensen occupied the opposing fullback inside, freeing Morris who blocked him. Morris then delivered the ball into the box, and thanks to a goalkeeper error, Aberdeen scored the equalizer.

Conclusion

In the end, Jimmy Thelin’s plan worked perfectly: Aberdeen won the penalty shootout against the strong Celtic — a result that fully confirmed their match plan focused on defensive stability. The 5-3-2 system was a well-thought-out strategy, especially effective in the first half.

However, Aberdeen still showed room for improvement with the ball. The substitutions late in the game brought fresh offensive energy, and the team did everything to push their attacking line forward. Although this created only a few clear chances, Aberdeen managed to reach extra time thanks to a goalkeeper error and eventually decided the match in the penalty shootout.

Ultimately, Celtic was clearly superior in individual quality across all positions. All the more impressive, then, that Aberdeen won the cup again after 35 years, securing international qualification. Considering the team lost consistency in the second half of the season after a strong first half and finished fifth—just outside of European qualification—this triumph is an extraordinary achievement.

VR: He works in analysis for a traditional fourth division club in Germany. He has a heart for English and Scottish football and loves to analyze football games.

SR: He studies history and philosophy, which can be noticed in parts of his writing. Besides his studies, he writes opponent analyses for a Swiss fourth division club and tries to watch every possible football match.

RO: He’s certain—he loves football. For 12 years, he’s tried to look at the game from every imaginable angle, all to ultimately figure out what it truly means to love football.

Feedback is welcome at: [email protected]

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen